GATHERING 5 Warwick Street London

Gathering and Workplace are delighted to present At Home, Everywhere and Nowhere, an ambitious solo exhibition shown collaboratively across both galleries. At Gathering, a larger-than-life sized inflatable sculpture of the artist fills the ground floor space, a gesture of spectacular theatricality. The bravado of this work is offset by the environments occupying Gathering’s lower floor: here, Barclay uses appropriated images and objects to negotiate between exposure and disguise, vulnerability and defence, inviting the viewer to entangle their own cultural perspective with the range of pop-cultural and art historical references encoded within his work. Through his reinterpretation of each gallery space, Barclay creates immersive landscapes in which conceptions of masculinity, alienation and desire are subverted as they are performed, leading the viewer into a shadowy world that feels both, strange and familiar.

On entering Gathering, visitors are confronted by the enormous underbelly of an inflatable Donald Duck sculpture. Lying face down, squashed in places by the gallery’s architecture, the overpowering scale of the figure becomes bathetic, a mixture of the monumental and the absurd. As the viewer is forced to edge around the mass of air and plastic, the figure reveals itself to be the artist dressed as Donald Duck - or, more precisely, the artist dressed as Elton John wearing the Donald Duck costume designed by Bob Mackie for a 1980 performance in Central Park, New York. This layering of guises and characters results in a choreographed exchange between concealment and display: the ‘real’ Barclay is obscured by the hyper-visibility of his overblown likeness. Near the head, a profusion of javelins introduces the threat of puncture and deflation; the inflatable’s tautness becomes its vulnerability. Barclay considers the inflatable as emblematic of the artist’s ego - both inflated and fragile. The aforementioned fragility is rendered visible by the nearby lightbox, displaying a nude self-portrait of the artist taken by fellow artist and activist Ajamu X. Holding an unguarded pose inflected with the grace of Classical sculpture, Barclay is shown tender and exposed, cradling his diminutive puppet-self. The inflatable work at Gathering builds upon Iceberg (2022), an earlier sculpture featuring the puppet of the same Barclay-as-Elton-as-Donald character suspended in a chartreuse Perspex box, shown at the artist's solo exhibition In The Name of the Father at the South London Gallery in 2022.

As the visitor descends into the lower gallery space, they become submerged in yellow light filtering through Perspex ceiling tiles, effectively inhabiting a scaled-up version of the vitrine housing Barclay’s puppet. Hanging low, the panels evoke an off-kilter version of the budget suspended ceilings found in corporate interiors, eliciting the uncanny claustrophobia of Floor 7½ in Being John Malkovich. Just as the puppeteer protagonist in the 1999 film crawls through a portal in his office to emerge inside the titular actor’s consciousness, the landscape that unfolds beyond the ceiling feels like a fractured insight into the artist’s head. Flashes of neon and the whirring of rotating machinery animate the environment like synapses; images, words and objects are scattered, unmoored from their expected functions and reappropriated to produce a map of personal signification. A leather jacket is adorned with a Barbara Hepworth sculpture and a Yorkshire pie, two emblems of Northern pride worn like a motorcycle gang insignia. Draped across the centre of the gallery, a decommissioned parachute is strung with neon signage spelling out the words ‘LIMP’, ‘PROUD’ and ‘REBEL,’ while a cardboard cut-out of a policeman is left to rotate mindlessly atop a robot vacuum cleaner; together, they present a dream-like vision of a fragmented urban environment.

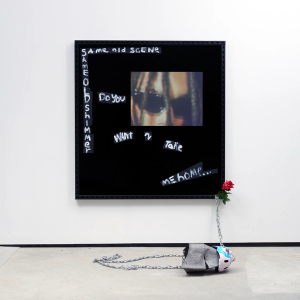

The pair of Dr Martens boots that dangle from the parachute act as a sartorial symbol, one that has migrated from industrial workwear to British youth subcultures to the proliferation of club culture in the 1980s and 90s. Minute differences in colour, lacing and style served to mark out a subset of Skinheads affiliated with the National Front from their left-wing or apolitical counterparts, an example of the semiotic approach to dress that runs throughout style subcultures. Barclay uses fashion as an entry point for the viewer, encouraging a sensitivity to the systems of language and symbols that underpin cultural production and shape individual identity formation. Stationed around the perimeter of the space are a series of vinyl works, framed with steel strut channels and embellished with UV prints on aluminium. The prints have been lifted from designer Hedi Slimane’s Autumn/Winter 2023 runway show for the luxury fashion house Celine: images of eyes, obscured by dark sunglasses and long fringes, blurred by motion. Slimane’s aesthetic is defined by lithe, nonchalant glamour, but has also been criticised for his rarefied vision of cool that does not extend far beyond white, rake-thin youthfulness. Barclay describes being both absorbed and repelled by the impenetrability of the models, stalking down the catwalk with an attitude aptly summarised by fashion critic Rachel Tashjian as ‘don’t look at me, but please look at me’ [Harper’s Bazaar, 9 December 2022]. This sentiment resounds in the tensions between exhibitionism, disguise and vulnerability, explored on the gallery’s ground floor, but is also played out in the materiality of the vinyl works. While the seductive gloss of their surface evokes the pages of fashion magazines, legibility is foreclosed; instead, the viewer is drawn into a confrontation with their own reflection - seeing and being seen, partially visible in the dark vinyl.

Text by Sybilla Griffin

Photography by Tom Carter